Women's Struggle to Become First Chair Trial Lawyers in Patent Cases

Patricia Martone

The underrepresentation of women in leading roles in law firms was an increasing focus of bar associations, law firms, and judges and courts. Innumerable articles were written, speeches given, and conferences held. However, in recent years, despite this attention, it became clear that women’s progress was not as it should be.

Preface

The subject of this article is rooted in my own experience. For 30 years, beginning in 1983, I was an equity partner in major law firms and a specialist in patent litigation. I was a pioneer among women patent trial lawyers. I tried my first case as lead trial counsel (“First Chair”) in 1987. I believed that the barriers I faced early in my career would be more easily overcome as more women entered the practice. The underrepresentation of women in leading roles in law firms was an increasing focus of bar associations, law firms, and judges and courts. Innumerable articles were written, speeches given, and conferences held. However, in recent years, despite this attention, it became clear that women’s progress was not as it should be. This led to my work at the Engelberg Center at the NYU School of Law and this article. I wanted to know if the percentage of women among First Chairs in patent litigation was improving over the years, and if not, why. To know the answers to my questions, I needed data.

I read relevant writings and reports about women’s progress in the law and gender equality in the United States. I was unable to find any public data which would help answer my question forcommercial litigation, much less patent litigation, in federal district courts around the country. This lack of data is very significant. If women’s service as First Chairs cannot be readily and reliably tracked, then we cannot know whether current diversity efforts are succeeding and what improvements should be made.

This led me to my own data gathering. I am deeply grateful to Lex Machina, which generously gave me complimentary access to its entire database of the court records of intellectual property cases, which begins in 2009. I reviewed the record of every patent trial in the years 2010 and 2019—over 200 cases—and determined the percentage of women among all of the First Chairs in those trials. As I shall explain, the results were disappointing. I compared the results I obtained with those compiled by authors writing about women arguing appeals in patent cases and women representing parties in proceedings held pursuant to the America Invents Act in the United States Patent and Trademark Office. I also conducted interviews of women lawyers, including six of the women First Chairs in 2019 patent trials.

I report on what I learned and the barriers I identified to gender equality in this practice and suggest a positive path forward of greater attention to the importance of diversity and inclusion.

I would like to thank the Engelberg Center and Michael Weinberg, its executive director, for their support and encouragement of my work reflected in this article. Thanks also to Professor Rochelle Dreyfuss, Professor Paul R. Gugliuzza and Dr. Julie Blackman for providing helpful comments. Finally, I express my appreciation to Lex Machina and its executive Joshua Harvey for providing me with complimentary access to the company's database of patent cases which was instrumental to my research.

I. Introduction

For trial lawyers, the ultimate career goal is to become a First Chair trial lawyer. First Chairs take the lead in formulating case and trial strategy, handling court room presentations and witness examinations, and communicating with judges and juries. In selecting litigation counsel for a case of significance, a client’s primary focus is on the attorney who will be First Chair at any trial, and, in particular, that attorney’s trial record. Whether or not a client actually wants to try the case, or hopes to resolve it pre-trial, that client knows that selecting a good First Chair will be important in achieving a good result no matter the stage at which a case is resolved.

Further, a trial lawyer’s strength as a First Chair directly impacts her ability to bring in new cases (known as making “rain”). Generating significant revenue is key to a partner’s status and compensation. This relates directly to another gender parity problem—the status of women partners in law firms and their compensation. Before there can be gender parity in compensation, there needs to be gender parity in opportunity. It is the pervasive lack of opportunity that is the focus of this paper.

I began traversing the path leading to First Chair status almost 50 years ago, when I graduated from the NYU School of Law in 1973. In 1983, I became a partner in the firm of Fish & Neave. I was the first woman in the United States to become a partner in a major patent law firm. From 1977 until my retirement from Biglaw at the end of 2013, my primary focus was patent litigation. Not just discovery and pre-trial motions, , but trial work. Many litigators rarely if ever actually try a case. I was a trial lawyer, and like all trial lawyers, from the time I was a junior lawyer, I aspired to lead trial counsel (“First Chair”) status on trial teams.

During the 1980s and 1990s I faced barriers affecting all women lawyers and struggled to attain the role of First Chair. I ultimately succeeded. During my law firm career, I was the First Chair in more than 45 cases, and tried 12 cases to a verdict or judgment, some as First Chair. I had a major role in the landmark trials in Polaroid v. Kodak (infringement of Polaroid instant photography patents) and NBA v. Motorola (intellectual property rights in the scores and statistics of NBA basketball games).

While the status of women lawyers in patent litigation has improved since the 1990s, despite the passage of decades, barriers still exist, and I continued to experience them during my career. There is widespread acknowledgment of women’s underrepresentation in leading roles in the legal profession generally. Many articles have been written and many conferences have been held about possible solutions to this problem. Bar associations conduct studies and have committees focusing on the progress of women. Many law firms have diversity officers and programs and promote their diversity efforts. Judges and courts have become sensitive to this problem and encourage counsel to give more courtroom work to younger and more diverse lawyers. Clients have demanded greater diversity from their outside counsel trial teams.

But from everything I heard or read, despite the public attention to gender disparity in law firms and in the courtroom, the needle of woman’s service as First Chairs, in litigation generally and in patent litigation specifically, was not moving. I wanted to help move that needle. All of this led me to the Engelberg Center at the NYU School of Law and my work on this paper.

My investigation revealed that, indeed, the needle was not moving. Lex Machina data established that in 2010, women comprised 8.1% of First Chairs at trial in patent cases. In 2019, women comprised 9.9% of First Chairs at trials of such cases. Plainly, despite all the talk, the needle barely moved over a 10 year period. At the current rate, it will take women at least 56 years to achieve gender parity as First Chairs in patent trials. These numbers are consistent with the related research of other investigators.

My study also concluded that in 2010 and 2019, women were significantly underrepresented in the category of First Chairs handling jury trials. Because jury trials are preferred in most types of patent litigation, this trend suggests a limit on women’s opportunities to serve as First Chairs. Another significant finding is that in 2019 trials, women tended to litigate patents in the life sciences area and not in the many other technologies that were the subject of patent trials that year. Although most of the women First Chairs in that year have undergraduate degrees in biology or chemistry, the women I interviewed discounted this credential as significant to clients. This issue of whether women are being held to a different standard as compared to men deserves further attention. If a lawyer’s undergraduate degree is of more significance to clients or firms for women as compared to men, the fact that the most popular undergraduate degree for women in STEM is life sciences suggests that fewer women are likely to be selected as First Chairs for cases involving technologies such as electronics, semiconductors, telecommunications, or computers. This would be another limit on women’s opportunities. This paper continues with an exploration of factors underlying the data, including a) entrenched gender inequality generally in the United States, b) the existence of implicit bias, and c) the structure of law firms, including an overemphasis on billable hours and the failure to put equity partners at the center of diversity efforts.

This paper concludes with a positive path forward focused on law firms and equity partners. That path includes the active involvement of equity partners incentivized by a partner compensation system that meaningfully rewards partners financially for providing mentoring, training, and client opportunities for diverse lawyers, including women, at both the associate and partner levels. Such a path does not need to result in declining profits. If properly conducted, these actions should be profit enhancing. The final recommendation is that law firms must employ quantitative metrics to track the progress of all lawyers, including diverse lawyers. Without meaningful data, it is impossible to track the success of diversity efforts.

II. The Methodology of the First Phase of My Investigation

A. Defining the Scope of My Investigation

To determine the progress of women’s status as First Chairs in patent litigation, data is required. But we want to collect the right data which most accurately reflects the path to First Chair. And, any analysis must be nationwide. Patent litigation tends to be nationwide practice. Patent trial lawyers are located throughout the country and travel to federal courts throughout the country.

In determining the data to collect, I also considered that the path to First Chair status is a long one, that patent cases are expensive to litigate and have serious business consequences for both sides. Damages can be very significant. Unlike typical commercial litigation, injunctions are available to end infringing activity. For these reasons, patent litigation has been referred to as “the sport of kings.”

As a consequence, clients want very experienced First Chairs. In my experience, it takes 15 to 20 years of experience after law school graduation for a trial lawyer to be ready to take on the role of a First Chair in significant patent litigation. This means focus on attorneys at the partner level. Clients also want First Chairs from firms that routinely handle major litigation in the federal courts, which have exclusive jurisdiction over patent cases. This means focusing on law firms that routinely handle significant litigation, including patent litigation.

I decided that ideally, I wanted to track the nationwide percentage of women among the following populations.

Law students

Lawyers in private law firms likely to handle patent litigation

Partners in law firms likely to handle patent litigation

Partners in those law firms whose practice includes patent litigation

First Chairs in patent litigation

I found considerable data for categories A through C. This data supports the widely known fact that women are underrepresented in law firm partnerships. Much has been written on this issue, and an analysis of the reasons for this gender disparity is beyond the scope of this paper. But data for these categories does provide context for the data I was particularly interested in—categories D and E. Women never get to categories D or E unless they pass through the gates of categories A through C. This paper focuses on the experiences of that select group of women who get to category D. If the percentage of women in categories D and E were comparable, then a particular focus of inquiry should be on getting more women to become partners and handle patent litigation. If, by contrast, the percentage of women in category E was meaningfully smaller than the percentage of women in category D, then the focus of inquiry should shift to the career development of the partners.

Despite the widespread recognition of the lack of women serving as First Chairs in patent litigation, and the noteworthy efforts of so many organizations, I found no statistically reliable data for categories D and E. I did find limited reliable data on the percentage of women who served as lead trial counsel in commercial litigation and, in one case, IP litigation (which includes trademarks and copyrights as well as patents). I also had some anecdotal media reports in my own files.

Ultimately, as I will explain in more detail below, because of the generosity of Lex Machina, which offered me the complementary use of their fulsome database on patent trials from 2009 to 2020, supplemented by my own experience as a trial lawyer, and other information that can be obtained from public sources including PACER, I was able to reliably prepare my own set of data in category E by determining the percentage of women who served as First Chairs in actual patent trials in 2010 and 2019. I was not able to develop a comparable set of data for category D.

B. Pre-Existing Data Collected by Others

Despite the limitations of the pre-existing data collected by others, it does provide valuable context for the Lex Machina analysis in terms of measuring the overall progress of women lawyers, particularly those wishing to pursue a career as a trial lawyer. For this reason, before proceeding to the Lex Machina analysis, I will provide an analysis of the most meaningful data sources, keyed to the categories described above.

1. Category A–Data on the Percentage of Women Among Law Students

Comprehensive data about the percentage of women attending law school can be found in the report entitled The American Bar Association’s Report, First Year and Total Enrollment by Gender 1947-2011 (“ABA Law School 1947-2011”). This data is based upon reporting by ABA accredited law schools. Given that the focus of my investigation is the period from 2010 to 2019, and that in my experience it can take 15-20 years to become qualified to be a First Chair, then it is particularly relevant to look at law school data for total enrollment during the years 1990-2004. I also reviewed additional ABA law school gender data for the years 2016-2018. The data shows that percentage of women law students enrolled in JD programs was never less than 42.5% (1990-1991) and had reached 47.5% by 1998-1999 and 48.7% by 2003-2004. By 2017, the percentage of women enrolled in JD programs had increased to 52.39%.

2. Categories B and C–Data on the Percentage of Women Among Lawyers and Partners in Private Law Firms

Data comparing the percentage of women among lawyers in private law firms to the percentage of women among partners in these law firms has been collected for decades. The result is always the same. The percentage of women among partners increases at a glacial pace and is always appreciably lower than the percentage of women among all lawyers at the pre-partner level in firms. Moreover, over some periods, the percentage of women among the ranks of associates declines. This is not surprising, given the gender disparity in career opportunities for women.

The American Bar Association Commission on Women in the Profession, Report to the House of Delegates (June 1988) (“ABA Women 1988”)

The first American Bar Association report on the status of women was based upon “open hearings … written testimony, reports surveys and articles” The report focused on the significant barriers to the overall success of women in the profession and did not address the status of women lawyers in specific practice areas.

According to this study, women comprised 25% of all associates but only 6% of all partners in private practice. In the top 250 largest law firms, these percentages increased to 33% and 8% respectively. These numbers reflect the very slow progress women were making in becoming partners in the 1980s.

The Glass Ceilings Report of 1995

In 1992, the New York City Bar Association engaged a study about how women were progressing at New York City’s largest law firms. The resulting Glass Ceilings Report, based upon data and interviews provided by eight “Wall Street Firms,” concluded that while women made up at least 40% of law school graduating classes, they were absent from the partnership ranks. In the year 1994, for example, 40% of the associates, but only 12% of the partners in these firms were women. The cause was identified as follows:

“…[s]tereotyping, traditional attitudes and behaviors towards women, often focused on women’s roles as mothers…”

Table 1. Slow growth in percentage of women in the partnerships of signatory firms.

| Year | Percentage |

|---|---|

| March 2004 | 15.6 |

| Jan 2006 | 16.6 |

| Jan 2007 | 16.6 |

| March 2009 | 17.8 |

| March 2010 | 17.5 |

| December 2011 | 18.3 |

| December 2013 | 18.8 |

| December 2014 | 19.4 |

| December 2015 | 19.7 |

| December 2016 | 18.6 |

Source: New York City Bar Association 2016 Benchmarking Report.

While it is 25 years old, this study provides an exhaustive analysis of the barriers women faced then and, in my view, continue to face now in achieving success in law firms.

The Best Practices Report of 2006

A New York City Bar Association 2006 Best Practices Report concluded that 10 years after the Glass Ceiling Report, “women remain severely underrepresented in the profession’s upper echelon.” This report stated that among 82 of the signatory firms to the New York City Bar’s Statement of Diversity Principles, the percentage of women attorneys in the pre-partner pool was 33.1% but the percentage of women partners was only 15.6%.

Benchmarking Reports-Law Firm Diversity

From 2004 to 2016, the New York City Bar Association published periodic benchmarking reports on the progress of women and minority attorneys. The 2016 report published the data in Table 1 on the percentage of women in the partnerships of signatory firms.

By contrast, the report found that the percentage of women first year associates was 50% in 2004 and 47.2% in 2016.

Focusing on 2010 and 2019—the years of my Lex Machina investigation—the report shows that for the year 2010 women comprised 17.5% of partners in the association’s signatory firms.

While there is no data for the years beyond 2016, given the trajectory of the data presented, it is reasonable to assume that the percentage of partners who were women in 2019 was approximately 20%.

From the perspective of this paper, this report has shortcomings. The data set is collected from large New York City firms, making it geographically limited. Further, during the period of time reported, not all of these firms had a patent litigation practice. Nonetheless, it is striking that even though these firms had a commitment to diversity, the percentage of women in their partnerships barely increased over a 12 year period. Such data demonstrates that a firm’s commitment to diversity is not, standing alone, sufficient to achieve meaningful diversity.

Law360’s 2020 Glass Ceiling Report

More representative nationwide data can be found in Law360’s 2020 Glass Ceiling Report. “Law360 reviewed [2019] data from more than 300 firms to develop the rankings. In order to be included in the review, law firms had to at least provide demographic data on their overall attorney headcount. Firms had to have at least 20 attorneys in order to be reviewed.” Almost all of the firms on the top 40 list have patent litigation practices.

The 2020 report found that in 2019 women made up 37% of all attorneys at the law firms surveyed. But by contrast, women “…represented about 25% of partners [and] 22% of equity partners…” The report observed that it “…shows that law firms continue to make only minimal progress in their efforts to dispel the barriers women face, especially as they move up the ranks.”

3. Categories D and E–Data on the Percentage of Women Among Partners Practicing Patent Litigation and the Percentage of Women First Chairs in Patent Litigation

The absence of reliable nationwide data for these categories underscores the problem highlighted by this paper. Diversity efforts to achieve more women First Chairs in patent litigation exist, but there are no public metrics to measure their success. As will be shown below, more recent studies of women in technology law practices and women in the courtroom in commercial litigation, albeit collected from disparate sources using disparate methodologies, suggest that woman are achieving First Chair status in commercial and IP litigation commensurate with the percentage of women in law firm partnerships. Obviously, both percentages are lower than they should be. But the small amount of anecdotal data I found, and my own experience, suggest that women have made even less progress in patent litigation.

The Early Years

We have already seen that in the 1980s women were just beginning to achieve law firm partnerships. The going was particularly rough in patent law. A 1992 article focused on the Bay Area in California reported that the leading intellectual property boutiques in the area had no women partners who practiced in the patent field. The article stated that the ABA Women 1988 report, supra, “shows that the association’s intellectual property law section in one of only six sections with no women officers in its last term and the only one to have had no women on its governing council in the previous year.”

In 1999, I was one of the women attorneys practicing in the patent field interviewed by Corporate Legal Times for its article on women breaking down barriers in patent law. In my interview, I summarized my view of the status of women in the law at that time: Martone notes the two women who sit on the U.S. Supreme Court now were unable to practice law at private firms after they graduated from law school. “That didn’t change until the 1970s. The issue for women in the law in the 1980s was, ‘Can we become partners?’ In the 1990s it’s ‘Can we be rain makers?’

The article also quotes me as stating that in my [New York-based] intellectual property firm of Fish & Neave, eight out of 44 partners [18%] were women. I recall that at the time, this was a substantial number of women partners, particularly for a firm specializing in patents. Indeed, it is a higher percentage than that prevailing in New York City firms five years later as reported in the Benchmarking Reports, supra at 12-13.

At Fish & Neave in 1999, women comprised 15% of the partners (33 men and six women) specializing in patent litigation. I was one of two women partners with First Chair litigation experience, and in addition had First Chair trial experience. About 12 men had First Chair litigation/trial experience. Therefore, for Fish & Neave in 1999, the percentage of women First Chairs in patent litigation was about 14%.

The first article I recall concerning women’s efforts to break into leading roles in patent litigation was published by The Recorder in 2003. The article concluded that while women were making progress in becoming partners in patent litigation practices, they were having a “hard time breaking into leading roles in patent litigation.”

“A review of 13 firms with top patent litigation practices shows that of 512 partners, 80 are women [16 percent]. And even fewer women–42–have been in a lead role on a case that went to trial [8 percent].”

The rest of the article suggests that lead role means a first or second chair role. For example, my firm, Fish & Neave is described as having 37 patent litigation partners, of which seven were women [19 percent]. Of those five were listed as having served as first or second chairs at trial. But in 2003, to the best of my recollection, I was the only woman who had First Chair trial experience. One other woman partner had First Chair patent litigation experience and went on to be a First Chair at trial. At that time, about nine of the male partners had First Chair patent litigation experience.

In sum, at Fish & Neave in 2003, the percentage of women First Chairs in litigation among all First Chairs in patent litigation was about 18% (two partners out of 11 partners).

Looking at the number of women First Chairs at Fish & Neave or anywhere else in 1999 or 2003 is interesting but flawed. For example, several women partners at Fish & Neave in those years were too junior to have the experience needed to qualify to be a First Chair. We need to move forward to a later time, when more women partners had the requisite experience needed for this role.

2005 to Date

Formation of the ChIPs Network—Tracking the Progress of Women in IP Law

In recognition that more attention needed to be paid to women’s progress in technology law, in 2005 a group of women in Silicon Valley founded an organization called ChIPs. ChIPs stands for “chiefs in intellectual property.” ChIPs describes itself as a “nonprofit organization that advances and connects women in technology, law, and policy. We seek to accelerate innovation through diversity of thought, participation and engagement.”

Among the organization’s activities is tracking the progress of women, racial and ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ+ lawyers in practices including intellectual property. The organization collaborates with Diversity Lab to produce the Inclusion Blueprint Report.

Diversity Lab describes the purpose of the Inclusion Report as follows:

The Inclusion Blueprint, a collaborative project between Diversity Lab and ChIPs, provides a first-of-its-kind tool to measure the representation of diverse lawyers and the career-enhancing inclusion activities that law firms can and should employ to ensure that historically underrepresented lawyers have fair and equal access to quality work, influential people, and other opportunities.

The Inclusion Blueprint Report was initially created by Diversity Lab and launched in partnership with ChIPs in 2018 to measure and track the gender diversity and inclusion in firm leadership and Intellectual Property practice groups in law firms. …The Inclusion Blueprint has since been expanded to track additional inclusion activities and to include underrepresented racial and ethnic lawyers, LGBTQ+ lawyers, and lawyers with disabilities in all practice groups…

***

By participating in the Inclusion Blueprint, your firm and practice groups will have a roadmap of meaningful actions to take to continue investing in diverse talent and ensuring fair and equal access to career-building opportunities for all lawyers. As part of this process, Diversity Lab will score each firm, allowing firms to compare themselves against their peers and the industry.

The Inclusion Blueprint Report is an ambitious and noteworthy approach to improving diversity in law firms. Participating firms must drill down in detail on their diversity efforts. With a few exceptions, however, it does not report on the result of the firms’ tracking efforts. It merely encourages firms to track. It is noteworthy that the authors of the report recognize that without data we cannot measure the true progress of women and minorities. But the data collected from tracking is not reported, and therefore remains soley in the possession of the individual firm performing the tracking.

The Inclusion Blueprint Reports provide limited data on the percentage of partners in participating firms who are women, using, in the 2019 Report, 30% as a desired threshold for partners. The 30% figure is derived from the “Mansfield Rule,” which was created by Diversity Lab.

This rule requires that the 30% number be achieved for both equity and nonequity partners. This threshold exceeds the actual percentages of women partners reported elsewhere. (See supra pp 11-13.)

The reports do not provide data on the percentage of partners practicing patent litigation who are women, or the percentage of First Chairs in patent litigation who are women. But they do provide insight into the data problems addressed by this article.

The 2019 Report is particularly useful because it covers the same year as my 2019 Lex Machina investigation. In accord with the conclusions of this article, the 2019 Report states:

[l]aw firms do not consistently track career-enhancing opportunities to ensure equal access across all historically underrepresented groups at the firmwide and practice group levels. (emphasis in original)

***

The least-tracked inclusion activities and practices at the practice group level for all historically underrepresented lawyers include:

- Litigation and/or other First Chair responsibilities

- Origination credit

The 2019 Report provides no data on tracking by practice groups identified as patent litigation. The two practices groups most closely related to the subject of this paper are Antitrust, IP, Privacy and Cyber and Litigation. But patent litigation is only a part of their story. And once again, the reported data shows only the percentage of firms engaged in tracking in those practice groups, and not the results of the tracking, For the first practice group, the report shows that 62% of the participating firms track “Women, Litigation/PTAB First Chair Responsibilities.” But for the litigation practice group, the tracking of this category falls to 43%. With tracking statistics like these, it is clear that law firms are ill equipped to track the success of their diversity efforts.

The Inclusion Blueprint Report also provides forwarding looking solutions to improving diversity based upon the data they collected. We will return to those later in this article. But for purposes of my study, the publicly available data was insufficient.

Recent Studies on the Progress of Women in Commercial Litigation

It was not until 2015 that the American Bar Association published a report of a comprehensive study of women as First Chairs in commercial litigation: American Bar Foundation Commission on Women in the Profession, First Chairs at Trial, More Women Need Seats at the Table (2015). (“ABA Women 2015”).

The study was described as “a first-of-its-kind empirical study of the participation of women and men as lead counsel and trial attorneys in civil and criminal litigation.” To the best of my knowledge, it is the first statistical study which reported on the percentage of women appearing as lead trial counsel in intellectual property litigation. This analysis was based upon a random sample of all of the cases filed in 2013 in the Northern District of Illinois using the PACER system. In determining these statistics, the study utilized the description of an attorney’s role based upon their self-designation in an appearance form.

The study separately tracks the gender of lawyers who appeared as trial attorneys, meaning that they had some role in the case, and those who appeared as lead counsel. It is not clear whether in some cases there was more than one lead counsel. The study concluded that only 23% of lead counsel in intellectual property cases were women. It is likely that the percentage of women serving as lead counsel in patent litigation is considerably lower. Intellectual property includes trademarks and copyrights as well as patents, and historically, the percentage of women practicing in patents has been less than the percentage of women practicing in trademarks and copyrights.

Significantly, the report also acknowledged that “…it could be argued that the gender difference [reflected in the report] roughly mirrors the difference between the proportion of men and women generally in the legal profession.” This mirrors the issue highlighted earlier in this paper. Is the lack of progress of women serving in the role of First Chairs caused by barriers leading to partnership, barriers affecting women partners, or both? supra at 8-10. This article suggests that it may be barriers leading to entry into the legal profession generally, but that question remains unanswered.

A second report on the progress of women attorneys in the courtroom can be found in a 2017 New York State Bar Association Report: If Not Now When? Achieving Equality for Women Attorneys in the Courtroom and in ADR. (“NYSBA Women 2017”).

This report, prepared by the Commercial and Federal Litigation Section’s Task Force on Women’s Initiatives, was based upon questionnaires sent in late 2016 to federal and state judges throughout New York. The report states that the “task force believes its survey to be the first study based upon actual courtroom observations by the bench. The study surveyed proceedings in New York State at each level of court-trial, intermediate and court of last resort- in both state and federal courts. Approximately 2,800 questionnaires were completed and returned.”

The most relevant statistics presented are for the percentage of women lead trial counsel in the federal district courts in New York, albeit for both criminal and civil cases. These are 24.7% for the Southern District and 20.8% for the Western District. While the methodologies and locations of the courts differ, it is interesting that these numbers do not differ significantly from the 2013 data contained in the 2017 ABA Report reflecting women serving as lead trial counsel in 24% of civil cases.

4. Conclusions to be Drawn from Pre-Existing Data

The foregoing discussion demonstrated that the collection of data about the progress of women in law by an independent investigator is inherently problematic. The methodologies used vary widely. Some surveys, like the ones conducted by the ABA, rely on select publicly available data about a specific jurisdiction. Others, like the NYS Bar Association Survey, rely on information provided by judges in specific jurisdictions. Organizations like the NYC Bar Association and ChIPs have been able to derive some information from firms. But the NYC Bar’s focus is on New York City, and their work does not focus on patent or even IP litigation.

ChIPs' investigations have the benefit of being nationwide and do focus on firms active in the technology space. But its investigations are not limited to IP litigation, much less patent litigation. And, of course, currently ChIPs' is not asking firms to report the results of their tracking efforts. Finally, while data about commercial litigation is helpful, there can be no one- to-one comparison with patent litigation. Because of the complexity of and stakes in patent cases (See supra at 8), the percentage of women among patent litigators is likely to be lower than the percentage of women among commercial litigators.

Despite these shortcomings, it remains worthwhile to chart this data as a prelude to discussing the Lex Machina analysis (See Table 2 charting total women enrolled in J.D. programs, percent women lawyers, percent women partners, percent women lead trial lawyers, and percent women IP trial lawyers).

Table 2. Progress of Women in the Legal Profession.

| Total Women Enrolled in JD Programs | Percent Women Lawyers | Percent Women Partners | Percent Women Lead Trial Lawyers | Percent Women Lead IP Trial Lawyers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988-1989 | 42.2% | 25% (“private practice”); 33% (“250 largest firms”) | |||

| 1995-1996 | 44% | ||||

| 2010 | 47.2% (2009-2010) | ||||

| 2013 | 46.7% (2011-2012) | 47.2% (1st year associates, NYC firms 2014) | 17% equity partners | 24% (Northern District of Illinois civil litigation) | 23% (Northern District of Illinois) |

| 2017 | 24.7% Southern District of New York; 20.8% Western District of New York, civil and criminal litigation (p. 16-17) | ||||

| 2019 | 50%+ | 37.2% | 22% equity partners; 25% all partners |

Source: Footnotes 53-55, and studies discussed supra.

This data suggests the need for continuing investigation on the progress of women in commercial litigation and whether, indeed, women have achieved First Chair status commensurate with their participation in law firm partnerships. If this is the case, then our focus on improving the status of women in private practice in commercial litigation should be on investigating why in 2019, more than 50% of law students but only 25% of law firm partners are women. But the focus of this paper is on patent litigation, and existing studies proved insufficient for purposes of this investigation. This led me to explore the possibility of creating a new data set focused exclusively on patent litigation.

C. The Inability to Find Reliable Statistical Data Led to Lex Machina

In the ideal world, an investigator would like to see information reported directly by individual firms. But that has its own issues. First, which firms should be included in any analysis? While it is fair to assume that most patent litigation is handled by AM Law 100 and 200 Firms, there are a number of excellent small litigation boutiques specializing in patent trial work. Second, each firm has its own internal organization, which makes it impossible to assume that practice groups are organized consistently across a wide range of firms. Third, when we talk about partners, do we mean only equity partners or should we include nonequity partners? Fourth, what do we mean by First Chairs? Typically, it is the lawyer who has the lead role in addressing the judge and the jury. But sometimes, there are co-lead counsel. Finally, if information is needed directly from law firms, the firms have to be willing to provide this information. This requires a firm’s recognition of the issue, willingness to own up to problems, and commitment to providing solutions.

Obviously, it is impossible for an individual investigator to conduct a meaningful nationwide survey of law firms. Therefore, an independent analysis of publicly available information is the only realistic, albeit time consuming, alternative. In my conversations with Michael Weinberg, the executive director of the Engelberg Center, it became clear that the best path forward was to determine the number of patent trials in a particular year and then to determine the identity and gender of the First Chair in each trial. By taking this approach, we avoid the problems of seeking this information from law firms.

This led me to Lex Machina, a company providing a legal analytics platform that allows the user to do comprehensive research into individual cases, rulings of courts and judges, and performance of individual attorneys. Its primary use is to provide information to predict and craft winning strategies in particular courts and before individual judges. It also allows investigation about historic rulings on liability and patent damages awards. Thanks to the generosity of Lex Machina, I was provided complimentary access to their extensive data base about intellectual property cases.

III. Lex Machina Data Reveals a Decade of Little Progress for Women First Chairs

A. Methodology

The data base at the time of my investigation in 2021 spanned the years of 2009-2020. Among the resources Lex Machina provides are the dockets for each case, and, except for confidential filings and some trial transcripts, a copy of every document listed in the docket. As described more fully below, I used this database to determine the number of cases in which women appeared as lead trial counsel in patent infringement and/or invalidity cases that were tried in the years 2010 and 2019, and the percentage of women lead trial counsel compared to all lead trial counsel for those same years.

1. Reason for Focus on 2010 and 2019

I chose 2010 because it was the last full year of district court litigation before the passage of the America Invents Act (“AIA”) in 2011. The America Invents Act provided for new procedures in the Patent Office, and in particular for PTAB proceedings to challenge the validity of patents and has had a procedural and substantive impact on patent infringement trials.

I chose 2019 because it is the last full year of trials before the March 2020 onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought trial proceedings to a halt around the country.

2. Determining the Number of Patent Cases Tried in 2010 and 2019

In order to determine the number of patent cases actually tried during each of these years, I used the following filters available on Lex Machina:

For 2010:

Federal District Court

Case Types: Patents

Case Tags: General Trial

Pending From: 2010 01/01 To: 2010 12/31

Trial Date From: 2010 01/01 To: 2010 12/31

For the year 2010 these filters yielded a total of 125 cases.

For 2019 I used the same tags for Federal District Court, Case Types Patents and Case Tags: General Trial. I changed the year in the Pending From and Trial Date to 2019.

For 2019, these filters yielded a total of 77 cases.

Using the docket information, I investigated whether there was indeed a patent trial during each of the 125 cases in 2010 and the 77 cases in 2019. Lex Machina has a very robust database of tens of thousands of cases and each case is unique. That means that Lex Machina needs to make many judgments in categorizing cases, and in a few instances, after reviewing the docket, I came to a different conclusion. For example, for 2019, I determined that there was no actual trial of patent issues in 10 cases categorized as patent cases by Lex Machina. In at least one such case, the patent issues were resolved on summary judgment.

I included all trials in my final numbers and did not distinguish between bench and jury trials. I included cases a) where trial started in 2010 or 2019 even if the trial did not finish until the following year, b) where the trial started but was not tried to judgment, and/or c) where there were other causes of action, such as contracts, provided that patent validity and/or infringement issues were part of a trial. I excluded a handful of cases where the only patents at issue were design patents. In my experience, patent cases based only on design patents are rare and clients have different criteria for choosing counsel for such cases as compared to utility patent cases.

When my analysis was complete, I reduced 125 trials to 104 trials for 2010 and 77 trials to 64 trials for 2019.

3. Identification of Lead Trial Counsel Opportunities in Each Case

To determine the percentage of women serving as lead trial counsel in a particular year, it was important to determine the number of lead trial counsel opportunities in each case. In the typical case, there are two such opportunities: one for plaintiff(s) and one for defendant(s). However, in some cases I encountered, there were multiple defendants each having their own counsel. In such cases, I assumed that each defendant had their own lead trial counsel, leading to more than two such opportunities in such a case. If multiple firms appeared for one party, I counted that as one opportunity.

Using this method, I determined that there were 247 lead trial counsel opportunities in 2010 and 141 such opportunities in 2019.

4. Identification of Lead Trial Counsel and the Gender of Lead Trial Counsel in Each Case

I then turned to identifying who was lead trial counsel and the gender of lead trial counsel in each case. For each case, I derived the following information from the Lex Machina database.

The docket number and court. This data was necessary if I needed to access PACER to find trial transcripts and other trial documents not available on Lex Machina.

Determining who was lead trial counsel for a particular party in a particular case was a more complex matter. Lex Machina provides a list of all counsel who appeared in a case. However, like court records themselves, lead trial counsel is generally not identified and there is no particular order to the list of counsel. There is also no identification in Lex Machina or PACER of counsel’s gender.

Based upon my experience, there are typically two types of counsel in a patent case: local counsel and national counsel. While local counsel may play an important role at trial in some jurisdictions such as the District of Delaware and the Eastern District of Texas, they are not typically lead trial counsel, although in a few instances they may serve as co-lead trial counsel.

Based upon my own personal knowledge of many of the law firms and lawyers identified and the docket information, I determined which firm(s) were national counsel in each case.

The most reliable source for determining lead trial counsel was the trial transcript, and I checked the transcript when available. Typically, the trial begins with lead trial counsel for each party identifying themselves and their team to the court. Then each side gives an opening statement, typically but not always presented by lead trial counsel.

Particularly for the year 2019, not all trial transcripts were available on Lex Machina. In a number of cases, I relied on minute orders routinely issued by some courts for each day of trial. These detailed minute orders identified trial counsel and in some cases the role of particular counsel (e.g., who gave the opening statement).

When trial transcripts and minute orders were not available, particularly for 2019, I often looked at the list of counsel on pleadings and papers filed immediately before or immediately after trial and checked it against the list of counsel provided by Lex Machina. Typically, the signature block on court papers contains the names of the firms serving as local counsel and national counsel and lists the names of the lawyers appearing as counsel. The top name on the list of national counsel is typically but not always lead trial counsel.

In some cases, at the end of the above review and in particularly in situations where there were multiple firms representing the same client, and/or when local counsel took a particularly major role at trial, it was still not clear who lead trial counsel was. In some situations, it did not matter for my analysis because all of the candidates for this position were men. Where the candidates included a woman, I consulted the woman’s firm biography. Sometimes the biography identified cases where a lawyer was lead trial counsel. I also considered the possibility that in some cases a party had co-lead counsel, whether in the same firm or different firms, and determined that if a woman served as co-lead counsel, I would count that as a woman serving as lead trial counsel. [Note, if there were two male co-counsel, then I designated lead counsel as male. If there was one female and one male co- counsel, I designated lead counsel as female]. When it was impossible to determine the role of a women who was possible lead counsel from Lex Machina documents, I used PACER to access trial transcripts, usually from the first or second day of trial. I also made use of the names of attorneys appearing on motions filed immediately before trial, where the first chair trial attorney is typically listed first. Finally, in some courts the LEAD ATTORNEY is specifically identified in court records.

Based upon the above analysis, I determined that women served as lead trial counsel 20 times in 2010 and 14 times in 2019.

5. The Data Shows that Women are Underrepresented in First Chair Roles and that Little Progress Was Made Over a 10 Year Period

My investigation concluded with the determination that the percentage of women lead trial counsel in 2010 was 8.1%. In 2019, the percentage was 9.8%

Table 3. Percentage of Women Lead Trial Counsel in Patent Cases

| Year | Number of Trials | Number of Lead Trial Counsel Opportunities | Number of Cases with Women Lead Trial Counsel | Percentage of Women Lead Trial Counsel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 104 | 247 | 20 | 8.1% |

| 2019 | 64 | 141 | 14 | 9.9% |

Source: My analysis of Lex Machina data.

As we have seen, women’s progress in obtaining leadership positions in law firms was a repeated subject of discussion and analysis during this 10 year period. Yet the percentage of women First Chairs increased by only 1.8% over a 10 year period, which amounts to a 0.18% average improvement in any one year.

Unfortunately, we do not have reliable statistics on the percentage of women partners specializing in patent litigation during these years. But if we assume that it is comparable to the 25% number reported by Law360 for all partners in 2019, these number show that women partners are lagging far behind their male counterparts in achieving First Chair status in patent litigation. As shown in the chart below, at the current rate of .18% per year, if the percentage of partners who are women is at 25%, starting from 2019, it will take women about 84 years to achieve equal participation with male partners in the role of First Chair. If we reduce the percentage of current women partners to 20%, that only reduces the time to gender parity to 56 years (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of years for women to achieve gender equality as First Chairs (2019- 2018).

Source: My analysis of Lex Machina data.

As preposterous as these numbers seem, they are consistent with the World Economic Forum’s 2021 calculation as the amount of time needed to achieve gender equality in North America. (See infra at 40-41.) These numbers also show that increasing the percentage of women partners only exacerbates the problem if there is a not a path forward to increasing the percentage of women First Chairs.

For those who may challenge these statistics as aberrational, I offer two recent studies reporting comparable data for other fora related to patents—The Federal Circuit and the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. In their article "Gender Inequality in Patent Litigation," Professors Paul Gugliuzza and Dean Rachel Rebouche of the Beasley School of Law at Temple University, the authors report that “…12.6 % of federal circuit patent case oral arguments were presented by women attorneys from 2010 through 2019. When limited to private sector attorneys, that figure drops to 8.9% ….” Government attorneys are properly excluded for purposes of this paper because they do not participate in district court patent litigation. Therefore. the most comparable number for the instant study is 8.9%, which is midway between the percentages I report of 8.1% (2010) and 9.9% (2019).

For arguments before the PTAB, we have the 2019 report by the PTAB Bar Association on Women at the PTAB. This study reported that women made up only 10% of attorney appearances during the years beginning in September 2012. An appearance is defined as being listed in mandatory notices as “lead or back-up counsel.” This statistic represents all proceedings, not just the ones that resulted in a trial. But once again it is consistent with the investigation in this article.

6. The Data Shows that Women Represented Both Plaintiffs and Defendants but were Significantly Underrepresented in Representing Parties in Jury Trials

In 2010, women First Chairs represented 11 plaintiffs and nine defendants in patent cases. In 2019, women First Chairs represented seven plaintiffs and seven defendants in patent cases. From this admittedly limited data, one can conclude that there was no meaningful difference among parties concerning the retention of women First Chairs.

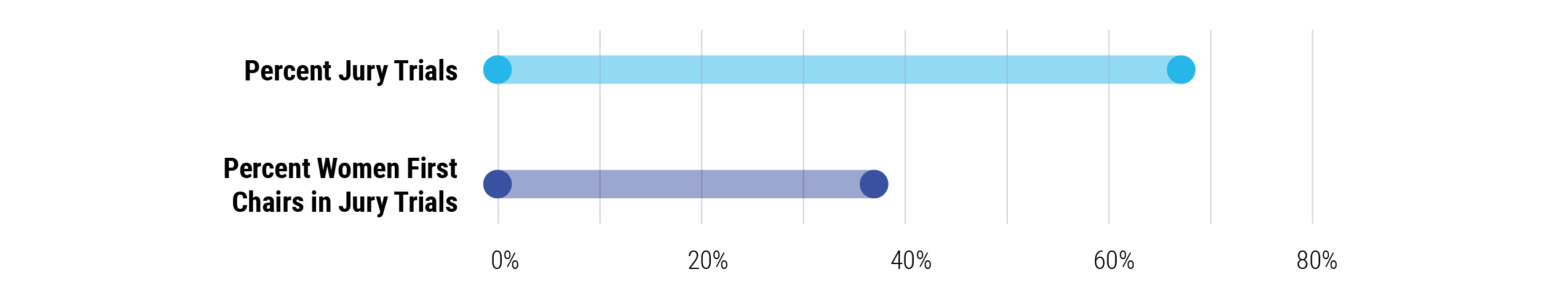

Figure 2. Women were still significantly underrepresented as First Chairs in jury trials in 2019.

Source: My analysis of Lex Machina data.

Of interest is the available data on whether the trials handled by women First Chairs were bench or jury trials. The swashbuckling male First Chair jury trial lawyer is what still comes to mind for many when it comes to jury trials, which is not a good fit for women.

This is an additional potential barrier for women in patent litigation because for many years, patent holders have preferred jury trials to bench trials. In its 2018 Patent Litigation Study, PricewaterhouseCoopers reported that during the years 2013-2017, 77% of cases were decided by juries. That same study reported that patent damages awards and patent owner success rates were much higher in jury trials as compared to bench trials.

Lex Machina data shows that in 2010, women First Chairs in patent cases represented parties in 13 jury trials and six bench trials. The fact that 68.4% of 2010 trials with women First Chairs were jury trials looks like progress. But in 2019, women First Chairs represented parties in nine bench trials and five jury trials. That translates into a jury trial percentage of 35.7%. Lex Machina data for 2019 demonstrates that this percentage is unacceptably low, because in that year, for the 64 trials resulting from my analysis, 67.2% were jury trials.

Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that at least for 2019, First Chair gender equality lagged for women in the jury trial arena. One possible cause is that in 2019 many women First Chairs represented parties in pharmaceutical “ANDA” cases, which are bench, not jury trials. An analysis of women’s progress in litigating patent jury trials is beyond the scope of this paper. But it is a worthwhile subject for further study.

7. In 2019, Women First Chairs, When Compared to their Male Counterparts, Were More Likely to Have a Technical Degree and a Degree Whose Subject Aligned with the Subject of the Patents in Suit

Another noteworthy finding from the 2019 data was the significant number of women First Chairs with science or technical degrees and the extent to which those degrees aligned with the subject matter of the patents in suit. This is a subject of interest to gender equality because of the chronic and obviously incorrect perception that women do not have the capability to understand and litigate complex technology. A woman with a technical degree undercuts that perception. But requiring a patent trial lawyer to have a technical degree and/or limiting his or her practice to a particular technology inherently limits that lawyer’s options. Complex questions present themselves: Have women been so limited, and if so, is that limitation reasonable or reflective of gender bias?

Based upon my experience, by 2019 the profession had moved on to the point where technical degrees, once considered a requirement for patent litigators, was no longer a requirement for First Chairs. The women First Chairs I interviewed largely agreed with my view (infra at 38). But I wanted to test this assumption with the 2019 data.

I examined the biographies of the women First Chairs to determine if they had at least a bachelor’s degree in science or engineering. Nine women had a science or engineering degree. Most were biology or chemistry majors, with one chemical engineering major. Three women did not specify the subject of their undergraduate degree, although one of those women has a BS degree. One woman had an undergraduate degree in political science.

vIn contrast, the male First Chairs had less technical education. Seven did not disclose the subject of their prelaw degrees, although one was an MIT graduate. One was a history major. Another majored in political science. There were only five men who explicitly disclosed a scientific degree. These were in the fields of medicine, chemical engineering, computer information systems, cellular biology, and electrical engineering.

It is fair to assume that the attorneys, male and female, who did not disclose their undergraduate majors did not believe it was pertinent to their chances of being hired as a First Chair. It is noteworthy that women First Chairs with disclosed technical degrees outnumber their male counterparts by almost two to one. Further, the women’s technical backgrounds tend to focus on biology and chemistry. The men’s technical backgrounds were somewhat more diverse.

This concentration in life sciences is consistent with the trends that exists for women in the science and engineering professions. A study by the National Science Board of women’s participation in the sciences and engineering show that in 2015, life sciences was the field with the highest percentage of women (48%). In that same year, women’s participation in the fields of mechanical engineering and electrical and computer hardware engineers was lower (9% and 10%-13% respectively).

It is also striking that women First Chairs were concentrated in life sciences litigation. Of the 14 2019 trials with women First Chairs, pharmaceuticals and Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) litigation comprised eight of the 14 cases. Biotechnology and medical accounted for three other cases. Two of the cases involved telecommunications and one involved mechanical technology.

Thus, the technical education of these women tended to track the types of patents they litigated. While there were a number of pharmaceutical/ANDA cases tried in 2019, there were also a number of trials involving electronics, semiconductors and computer technology. None of this latter group of trials had women First Chairs.

I do not mean to suggest that all is smooth sailing for women interested in life sciences litigation. Recent studies show that women are chronically underrepresented in pharmaceutical patent practice of all types. My only point is that the situation is even worse in other areas of patent litigation.

This exclusion of women from litigation in technical subject matter is a critical barrier to women seeking a First Chair role. The technical subject matter of patent cases is ever changing. From a commercial perspective, clients engage in high stakes patent litigation over valuable products. Those products change over time as technology and its commercial value changes. Even women lawyers with a technical background need to litigate cases in a broad range of technology to be able to have the same opportunities as men to achieve First Chair status.

While this data is limited to one year, it raises the suspicion that there is gender bias surrounding the qualifications required of women First Chairs and possible restrictions on the subject matters of patent litigation that they handle. And, when we speak of possible gender bias around a lawyer’s technical background, whose bias are we referring to—the law firm and its lawyers or the client? In my experience, even if a technical background is not required, some clients do express a preference as to whether their lawyers should have a technical degree. If the clients prefer a technical degree, they may also require a degree in a particular science or engineering subject. In a competitive environment, law firms want to field the best-possible teams to win a pitch. Do firms or clients apply their standards differently to men as compared to women? I have not collected sufficient data to answer that question. But the data from 2019 suggests these issues merit further attention.

IV. Getting Behind the Data: Reasons for the Stalemate

A. Same Old Same Old?

When I began thinking about the reasons for little improvement after so much effort, I was of course informed by, but did not want to be limited by, my own experience. I decided to interview some of the women First Chairs in 2019 trials. I will soon discuss those interviews.

But first, I would like to review some of the many reasons for women’s lack of progress put forth in earlier investigations. Such a review provides a basis for comparison with the realities of the world today. One of the most comprehensive discussions of the barriers can be found in the 1995 Glass Ceilings Report (supra). In my view, that report accurately summed up the problems that I and other women in law firms faced at the time. These problems included:

Generational issues between male partners and female lawyers about balancing family needs and the firm’s economic needs.

The tendency of male lawyers to mentor younger male lawyers because they remind them of themselves at a younger age.

Concerns of male lawyers about the appearance of a close personal relationship between them and younger female lawyers.

Women perceived as less effective than men at rainmaking.

Women seen as problematic employees with special needs (another way of criticizing the demands of family and motherhood).

The problems of part-time work, including undesirable assignments and getting “off the partnership track.”

Issues of personal style for women—being too tough or not tough enough.

Sexual harassment.

When I left Biglaw at the end of 2013, it was my sense that there was some improvement. The law and law firms were taking a strong stance against sexual harassment, and partners could be fired for being harassers. Yearly harassment training was mandatory. Men were more comfortable working with women. More women were choosing to practice patent litigation.

I explored my views and my personal experiences in my 2014 article entitled "Reflections on One Women’s Legal Career and the Critical Importance of Mentors." The article made two main points. The first is that good mentoring is the key to becoming a First Chair. By mentoring, I meant that partners groomed you for the role by providing you with successively more sophisticated work and responsibility and taught you how to handle both. I summarized my own experience as follows:

“…while my career path was hindered by my gender, it was also positively affected by the help of mentors, all of whom were men.”

My second main point was that motherhood presented serious and often at the time insurmountable challenges to women seeking to become trial lawyers. I am not a mother. My views were based upon the experience of women associates working on my litigation cases who were mothers.

Those women working part time had an inflexible end of the day at the office, unless they had live-in childcare or spouses who took the main responsibility for childcare. Single mothers working full time also had many childcare responsibilities. I wanted to work with these women and wanted to carve out realistic roles for them. My strategy was to make sure that the women in this situation were one of several associates working on a case, so that there would always be a backstop. And it affected their assignments. Patent litigation is a national practice. Regardless of where a case is pending, depositions take place around the country. Women with children working part or full time and who do not have a backstop at home cannot spend a week on the road taking depositions.

B. My Interviews with Women First Chairs in 2019 Trials

To get an up-to-date view on what was and was not working in terms of career development for women who wanted to be First Chairs in patent litigation, I decided to interview some of the women who were First Chairs in the 2019 trials I investigated. It is sometimes said that history is written by winners. In my investigation, that was necessarily true, because there is no reliable way to track the career path of women who did not succeed in becoming a First Chair. In the summer of 2021, I conducted Zoom interviews with six women who were First Chairs in patent cases in 2019. Five of them were partners in an AmLaw 100 or 200 firm. A sixth was a partner in a well-regarded regional firm. Each interview lasted at least an hour and the discussions were open.

I did not interview any of the First Chair women in 2010 trials because of the intervening period of time. Also, in 2010 I was still an active trial lawyer and have personal knowledge of my own experience and that of former colleagues.

I enjoyed these interviews with these exceptionally accomplished women lawyers. They were also very resilient, bouncing back from adverse circumstances and juggling careers and family life. After I was done, I wondered if these women were “superwomen” and more exceptional, on average, than the men who were First Chairs in patent trials in 2019. Some of the women I interviewed thought this to be the case. This article cannot answer this question with a data- driven analysis. But I mention it to point out the obvious—women may need to be more qualified than their male counterparts to achieve First Chair status.

In formulating the questions for my interviews, I wanted to explore both the positives and negatives of these women’s experiences. I also wanted to be informed but not limited by my personal experience. The following is what I learned.

1. Gender Bias

The interviews revealed that some of the partners had experienced the same type of gender bias that was identified in the 1995 Glass Ceilings Report. This included clients dismissive of ideas coming from women and clients unwilling to take a “chance” on women lead trial counsel in high-risk cases (litigation funders were identified as one such type of client). Examples also included mentors who did not think you could really be a First Chair, and internal criticism of the partner as “outspoken.” One partner reported that she had not experienced gender bias.

2. Mentoring

Mentoring is a word that can have multiple meanings. Mentoring can simply be service as a formal or informal advisor to young lawyers. But my definition requires that a mentor at least provide you with work, teach you how to do the work, give you responsibility, and serve as a sounding board. In my personal experience, mentors groomed me for partnership. When it was my turn to mentor, it was my turn to groom associates for partnership.

By and large, the women I spoke with have similar definitions. Mentoring for this group included senior lawyers who provided opportunities, taught you how to be a trial lawyer, let you run with a case, and were available for consultation. Mentoring also included practice group leaders who put you in front of clients. Mentoring includes helping lawyers navigate firm politics and manage their time effectively. While my sense was that these women were committed to being mentors, their experience as mentees was not uniformly happy. One woman spoke of a mentor who “turned” on her. Another spoke of a mentor who gave her opportunities but at the same time made plain that he did not think she could really be a First Chair. There was also mention of internal firm politics or organizational issues that made finding a mentor difficult.

Based upon my experience, these bumps in the road are not unusual. But each of these partners found a solution, by taking actions that included finding new mentors in their current firms, moving to a new firm, becoming a part of formal and informal networks, and seeking their own clients.

3. Motherhood

Turning to the challenges of being a mother and a trial lawyer, I learned that motherhood was not the barrier I thought it was, that the partners I interviewed handled associates who were mothers better than I did, and that improvements in technology were helpful to managing a career and being a mother. Five of the lawyers I spoke with were both mothers and successful trial lawyers. These lawyers became mothers at varying times in their careers. Some had their first child as an associate, others waited until they were partners. At least one worked part time for a while. Others never stopped full-time practice. Their childcare arrangements varied, with nannies, grandparents, siblings, and supportive spouses (including one stay-at-home dad) all in the mix.

Each family came to its own conclusion as to how to deal with the demands and stresses on a mother who is also a trial lawyer. But the takeaway here is that the lawyers and their families found a way to accommodate these demands and stresses. I also asked each lawyer about the current perspective of women associates who are or want to be mothers, and the counsel they provide to these associates. By and large, the lawyers I interviewed counseled their women associates who wanted to be trial lawyers that they should not hesitate to have children, but that they needed an effective support system in place and an understanding spouse. One lawyer observed that the more children you have, the more your career will be impacted, but, at the same time, three of the women I spoke with had at least three children.

In terms of part-time work for women lawyers, these partners did not see it as a problem. At least two said that a lawyer’s part-time status did not affect the nature of the assignments they were given.

The advancement of technology permitting effective out-of-office work has increased in recent years, and particularly during the pandemic. Showing up at the office every day is at least temporarily a thing of the past for both men and women. The partners I interviewed believed this gave women more flexibility in their practice and made it easier to be a mother.

An issue I discussed with one partner, based upon my personal experience, was the response of the rest of the trial team to situations where a full- or part-time lawyer who is a mother needs to deal with an emergency or limit their work time. She responded that today, all associates, male and female, want work flexibility. The lawyers on her teams are used to working cooperatively to fill in for mothers in these situations. The team members who are not mothers want the same flexibility and receive the same flexibility when they have a personal matter to attend to.

Finally, one partner pointed out that men now take paternity leave, which reduces any stigma attached to women who take maternity leave. However, she also observed that men tend to keep on working during their leave.

4. Importance of Technical Background

Every partner I interviewed had an undergraduate degree in science or engineering. There was general agreement that a technical degree was not necessary unless required by clients. But several partners said it was helpful with clients and helped them get the case they tried in 2019. Two partners said that it helped with cross-examination and with thinking on your feet generally during trial.

5. Firm Initiatives and Organization

All of the firms in which the women were partners had some form of diversity and/or career development initiative. Only one partner could identify any initiative particularly directed to women who wanted to become First Chairs in patent litigation. While it appeared that practice group leaders in these firms were mindful of, and collected information relevant to, the issues raised by my investigation, no one could identify any formal statistics kept by the firm of the type I sought.

I also questioned the partners about how the structure of the firms might affect the opportunities given to women striving to be First Chairs in patent litigation. One issue I was particularly interested in was the degree to which practice group leaders could affect the team of lawyers put forth to clients in a pitch. In some firms, the lawyer with the client relationship has the exclusive authority to decide who is to be included in a pitch and what their roles would be. Practice group leaders stepped in when the lead partner asked for assistance in assembling a team, or when the opportunity to pitch came directly to the firm or to a partner in another practice group. In other firms, practice group leaders had more of a role in deciding the lawyers on a team and their roles. One partner mentioned a pro-active practice group leader who encouraged her to take on First Chair roles.

Another structural factor which arose in my interviews was firms which had both salaried non- equity partners and equity partners. In such firms, the partners emphasized the need to have the non-equity position be treated as a steppingstone to equity partnership and not a dead end.

Several partners mentioned firm partner compensation strategies as helpful to career progress. In one firm, mentoring of other lawyers was a compensation factor. In a second firm, helping other partners was a compensation factor.

6. Conclusion from Interviews

On the whole, I found this group of women to be positive about their futures and those of more junior women patent trial lawyers. It was encouraging to find that motherhood was no longer the insurmountable barrier to being a trial lawyer. In terms of the attributes contributing to success, it was obvious that these women had much persistence, determination, and talent. I also found the same contributing factors mentioned in earlier studies and my own experience. These included a supportive family structure, the opportunity to get the experience they needed to qualify to become a First Chair, attracting their own clients, and having a firm structure to encourage their development as a First Chair trial lawyer. These last three are clearly attributes which require the cooperation of their firms, or at least some partners in those firms. Law firms know this. It has been the subject of discussion for at least a decade. Yet, what has been done so far is clearly insufficient. I will revert to these points when I discuss A Positive Path Forward, infra at 45-49.

V. Why Change is Hard

A. Societal Barriers

Previous studies about women’s progress in the law have not given sufficient attention to the societal factors affecting the position of all women in the United States. Americans may think that we live in the greatest country in the world, but that is simply not true for women.

The World Economic Forum, sponsor of the Davos meeting, publishes a yearly Global Gender Gap Report. The report ranks the countries of the world in four different categories and provides an overall ranking. The four categories are Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment. Table 4 shows the ranking for the United States for selected years from 2013-2021.

The chronically disappointing level of, and largely downward trend in, gender equality rank in the United States is remarkable. In particular, the persistent decline in rank for the United States in Economic Participation and Opportunity underscores the problem that aspiring women trial lawyers face: the “glass ceiling”. The 2021 report observes that:

“[T]he limited presence of women in senior roles shows a persistent ‘glass ceiling’ is still in place even in some of the most advanced economies. For instance, in the United States, women are in just 42% of senior and managerial positions…”

Table 4. US rank in Global Gender Gap Report for selected years 2013-2021.

| Category | 2013 | 2016 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Participation and Opportunity | 6 | 26 | 26 | 30 |

| Educational Attainment | 1 | 1 | 34 | 36 |

| Health and Survival | 33 | 62 | 70 | 87 |

| Political Empowerment | 60 | 73 | 86 | 37 |

| Overall | 23 | 45 | 53 | 30 |

The position of the United States continues to decline.

Source: World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report 2021.

The 2021 report concludes that the wait time to achieve gender parity worldwide increased from 99.5 years to 135.6 years. The wait time for North America was determined to be 61.5 years. This number is within the range of the 60-89 years I calculated to achieve gender parity for First Chairs in patent litigation at the current pace of improvement.

One important requirement for achieving economic gender equality is a legal system that supports gender equality. Here again we fall short. The legal system in the United States has not been supportive of that goal. Most recently, Americans were shocked by the Supreme Court opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization where the Court overturned the constitutional right to abortion set forth by the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade.

The result of this decision is a major setback for women’s healthcare.

Further, “unlike nearly all other industrialized nations, the US does not have national standards on paid family or sick leave, despite strong public support.”

Finally, women have endured a decades-long unsuccessful struggle to put an Equal Rights Amendment in the United States Constitution. Eighty-five percent of the member countries of the United Nations have an equal rights amendment in their constitutions. But the United States remains an outlier.

You might be wondering what all of this has to do with the progress of women trial lawyers. It matters because it affects the way that men and women are raised and educated, and the way the society we inhabit works. Although law firms offer generous benefits and tout their commitment to diversity, in the world at large, lawyers live in a country that tolerates a greater degree of gender inequality than that tolerated in many other countries in the world.

A recent example of how societal factors impact women lawyers is the degree of burnout experienced by women lawyers during the COVD-19 pandemic. On May 26, 2021, at a New York City Bar Association program entitled "Women Leaving the Law During COVID-19; Why Is It Happening and How Do We Fix It?" panelist Vivia Chen reported that a survey showed that 35% of women in the law were thinking of leaving the profession and observed that mothers of school-age children were particularly affected by the burden of home schooling.

Long-term societal tolerance of entrenched gender inequality inevitably results in “bias in the air,” or implicit bias:

“Implicit bias is often defined as being prejudiced or unsupported judgments in favor of or against one thing, person or group compared to another in a way that is usually considered unfair. This kind of bias occurs automatically as the brain makes judgments based on past experiences, education and background.”

Implicit bias affects the behavior of everyone in the firm, as well as clients, judges, and juries. It is not enough to prohibit explicit bias. Gender equality in the law firm will not be achieved unless firms keep gender equality issues at the forefront of the minds of those who have the power to end gender inequality. Those people are law firm equity partners.

B. Barriers Created by the Structure of Law Firms